Over the past ten years, Leonardo Frigo has dedicated his art and craftsmanship to exploring Dante’s Divine Comedy – a literary masterpiece that, more than 700 years after its publication, remains one of the most influential works in history.

His journey began with a stunning series of hand-painted violins, each depicting a canto from Inferno, resulting in 34 unique pieces. His latest work, however, takes Dante’s vision a step further: a handcrafted globe that brings to life the fascinating geography imagined by the Divine Poet, which we have described in this article.

Dante’s Globe is a truly one-of-a-kind creation, bridging two invaluable traditions. On one hand, it revives Dante’s distinctive vision of the world; on the other, it is crafted using long-lost globe-making techniques, thanks to an extraordinary historical source: Epitome Cosmografica, a 17th-century tome written by Vincenzo Coronelli – a Venetian friar who became the most renowned globe-maker and cosmographer of his time.

In this interview, Leonardo retraces his artistic journey, sharing what drew him to work on Dante’s Divine Comedy and the art of globe-making, as well as the challenges, discoveries, and moments of reflection encountered along the way.

Dante and the Globe: Turning the Divine Comedy into a Map

What drew you to craft a globe based on Dante’s masterpiece?

For the past fifteen years, Dante has been an inexhaustible source of inspiration for me, particularly with the Divine Comedy, though other works of his have also influenced me. However, my focus has always been the Divine Comedy.

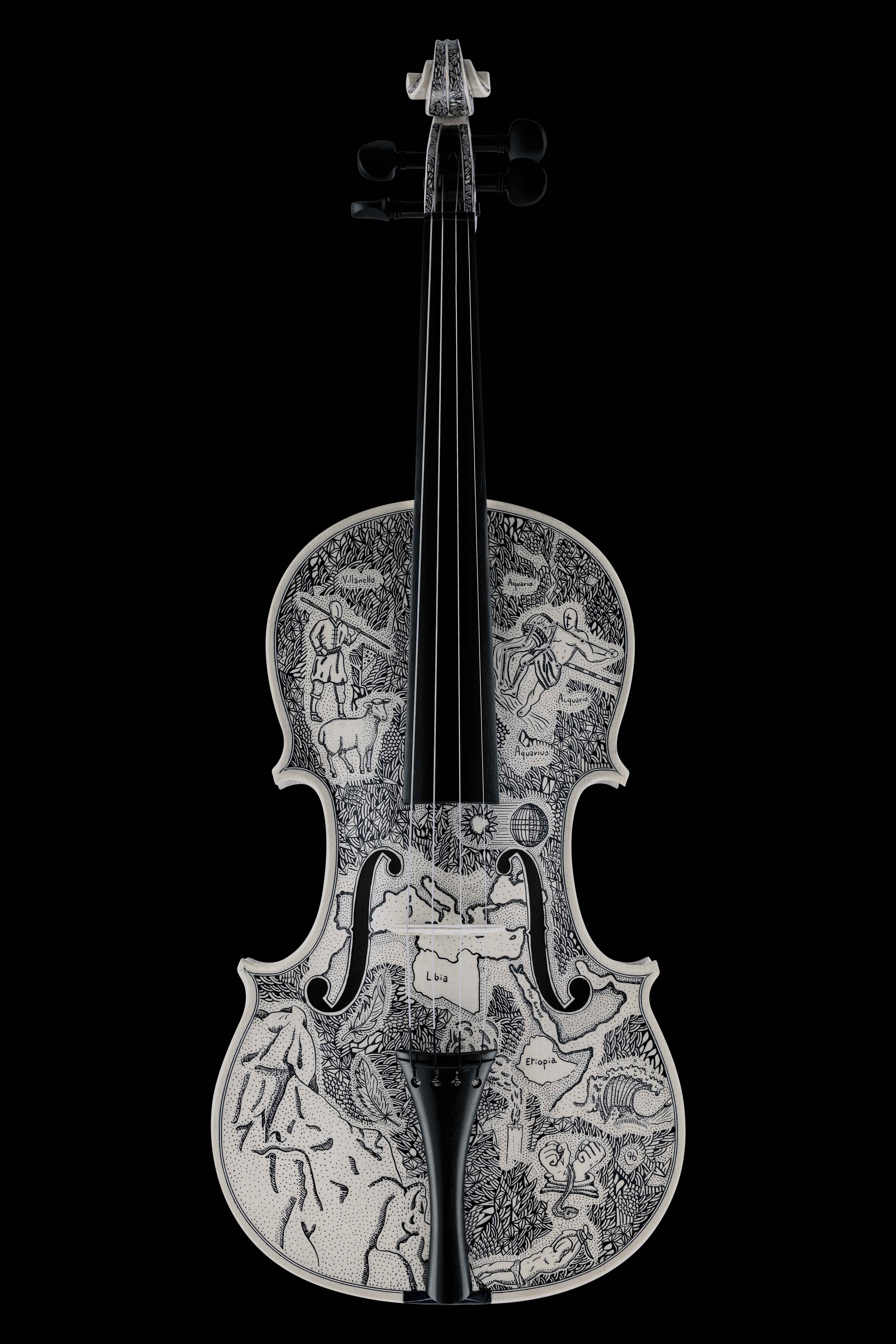

In my previous project, I painted 34 instruments, 33 violins and a cello, meticulously illustrating the entire Inferno of Dante. Each instrument is adorned with scenes, names, and significant quotations, mirroring the 34 cantos of Inferno. The cello represents the main canto and contains Dante’s biography, while the 33 violins narrate the rest of the work.

My fascination with Dante dates to my childhood. I clearly remember the first time I saw the Divine Comedy in an illustrated edition for children. I was five or six years old, and those images left a deep impression on me, particularly those depicting Inferno. The damned souls engulfed in flames, the dramatic scenes… I was immediately captivated.

Over the years, as I found my artistic path, I wanted to create works that were deeply connected to our culture and history. That is why I chose to create works that were not merely pieces of art but also had an educational value. My violins are not just painted; they tell the story of the Divine Comedy through their illustrations. From this idea, the desire to embark on a new project arose: Dante’s Globe.

After five years spent painting Inferno, the next step seemed obvious: working on Purgatorio and Paradiso. However, by that point, I had already delved into Dante’s geography through the violin project. In his work, Dante mentions numerous geographical elements: rivers, mountains, cities, even Ulysses’ journey beyond the Pillars of Hercules and into the ocean. There is a true Dantean geography embedded in his verses.

At that moment, I asked myself: Why not create a globe that represents Dante’s geography? I searched for an existing Dante’s globe, butI found that no physical representation of this universe existed.

During this time, I discovered Vincenzo Coronelli, the renowned Venetian cartographer and globe-maker of the 17th century, along with his manual, Epitome Cosmografica, which describes the process of constructing globes. This led to the idea of creating a project titled “The Globe: From Dante to Coronelli”, in which I aimed to combine Dante and geography with Coronelli’s artisanal techniques.

The goal was to establish a dialogue between two figures and two cities: Florence and Venice, Dante and Coronelli. More than just a work of art, I wanted to create an object capable of explaining both Dante’s geography and universe and the traditional craftsmanship behind historical globes.

Throughout the years, while working on the violins, I collaborated with a luthier, who handled the craftsmanship while I focused on the artistic side. I have always considered artisanal craftsmanship a fundamental element of my work, and with the advent of artificial intelligence, I have reflected on how crucial it is to preserve manual skills, both from an artisanal and artistic perspective.

Thus, Dante’s Globe was born from the fusion of Dante, Coronelli, art, craftsmanship, and the revival of a nearly lost art – that of globe-making.This project represents a harmonious blend of historical research and the recovery of traditional materials and techniques.

How did you balance the duality of symbolic and geographical elements in the globe’s design?

In my research, I relied on numerous historical sources. There have been countless studies on Dante’s universe conducted over the centuries. Even Galileo Galilei dedicated lectures to the size and shape of Inferno. Before him, Antonio Manetti, a 15th-century scholar, explored these topics, and many others have continued to delve into Dantean geography up to the present day.

For example, there are recent studies published in the last three or four years, and institutions such as the Galileo Museum in Florence preserve documents and research on this subject. The wealth of references was extensive, but for that very reason, the challenge became even more complex.

Also, I sought to work by immersing myself in Dante’s perspective and his vision of the world. I tried to reason with the scientific and geographical knowledge of his time, attempting to understand how he might have conceived the universe.

It is important to remember that the Middle Ages was an era in which religion, myths, and local legends coexisted, all of which influenced people’s perception of geography. Dante had to be careful not to mention certain elements to avoid ambiguities or confusion in his narrative.

Therefore, the most fascinating aspect of this work was precisely trying to see the world through Dante’s eyes, balancing his symbolic geography with our own.

Bringing Dante’s Universe Back to Life

Do you see the globe as a continuation of this work?

The 34 instruments and the globe represent my personal interpretation of the Divine Comedy.

In the globe, Inferno is not actually depicted visually. At first, I considered finding a way to include it inside, but in the end, I chose not to. I preferred to maintain Dante’s perspective from Paradise, as he gazes down upon the Earth, considering that I had already told the story of Inferno through the violins. I see these projects as part of a single artistic journey, a unified visual narrative of the Divine Comedy.

If I were to imagine an exhibition bringing together all my work on Dante, it would be a pathway that begins with the violins, which illustrate Inferno with their black ink engravings on wood – a darker, more dramatic aesthetic, in keeping with the themes of the work. Next comes the globe, representing Dantean geography, with the mountain of Purgatory attached to it. Finally, the journey concludes with the table, symbolising Paradise, characterised by brass rings orbiting around the globe.

So yes, I see the globe as a natural continuation of my work on Dante. It is part of a single, cohesive project that has accompanied me for around ten years, from the moment I first conceived the Inferno to the completion of the globe – a true Dantean journey.

Was creating Dante’s globe a greater artistic challenge?

To be honest, calling it a challenge would be an understatement. After completing the Inferno Dantesco with the 34 instruments, I found myself facing a great struggle. When I finished that project, I went through a sort of personal crisis, asking myself: Now? What do I do next?

I believe that any artistic project – whether it be a painting, a sculpture, or a book – accompanies you in your daily life, almost like a traveling companion, sometimes a friend, sometimes an adversary. Once I had completed the work on the violins, I felt temporarily lost, searching for new inspiration.

When the idea of the globe emerged – from the combination of Dante, Coronelli, and geography – I immediately realised that it would be an even more complex project than Inferno. The greatest difficulty lay in the research of materials and the techniques required for its construction.

After finding the manual Epitome Cosmografica, I began reading it and quickly realised that I had no idea how to craft a large wooden sphere. I didn’t know which type of plaster to use, which paper would be most suitable, how to create copper engravings, or how to proceed with printing. There were countless technical aspects to learn.

It was an intensive process of study, but luckily, my method of reading and analysing the Divine Comedy was already established thanks to my work on the violins. When working on the instruments, I had been annotating the rivers, mountains, and cities mentioned in the cantos, so that a research method was already in place.

The real difficulty was bringing all the pieces together and creating a globe that also had a scientific foundation. I did not want to simply craft a visual work of art – I wanted to give historical and geographical justification to every element.

For example, Dante describes Jerusalem as the centre of the inhabited world and places Purgatory at its antipodes. My task was to demonstrate and justify these statements by finding references in past Dantean studies. This was one of the most challenging aspects of the project because there are differing theories on many aspects of Dante’s geography.

I spoke with several professors and scholars, and they often had very different perspectives. I had to find a balance between their interpretations and my own artistic vision. In some cases, my perspective as an artist and craftsman clashed with certain academic theories, and I sensed a degree of resistance from some scholars.

So yes, creating Dante’s Globe was an enormous challenge, not only from a technical and artisanal standpoint, but also in terms of research and source validation.

The Influence of Vincenzo Coronelli and Globe-Making

What aspects of Coronelli's philosophy resonated most with you?

Years ago, while researching maps, I came across an article about Vincenzo Coronelli. As I read it, I discovered that he was a Venetian friar, born and died in Venice, and this immediately caught my attention – especially because I studied in Venice, and I am Venetian myself. In a way, Venice feels like home to me.

As I delved deeper into his history, I realised that many of the globes I had seen in museums and photographed over the years were his work. This sparked a deep curiosity in me, leading me to travel to different cities to see his globes up close and to study his figure.

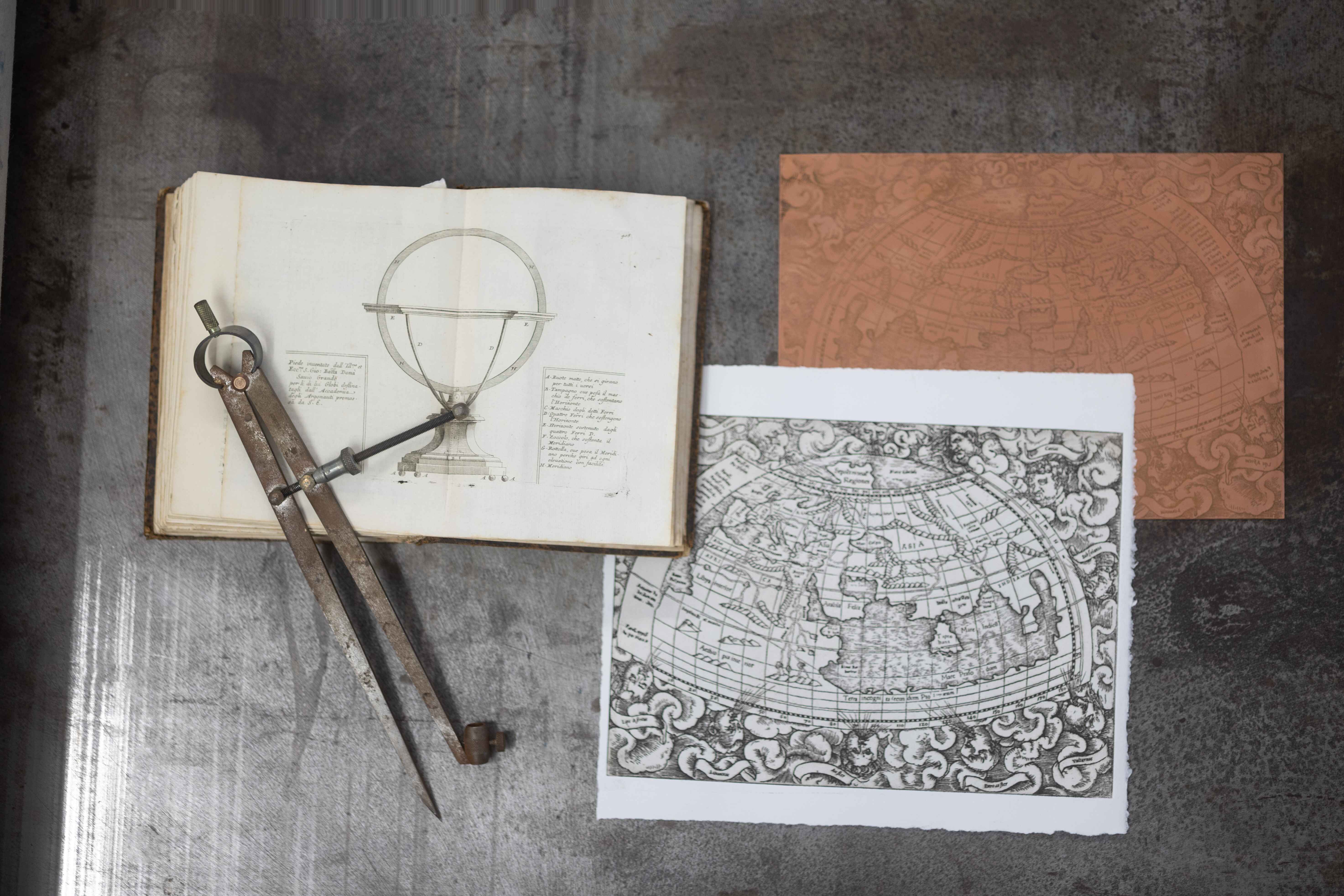

I began analysing not only the globes, but also his manual, the Epitome Cosmografica. This text is much more than a mere guide to globe-making: the first two sections focus on geography and astronomy, and it serves as a comprehensive collection of his lessons and research. What struck me most about Coronelli was the sheer beauty of his maps and globes, but also his commitment to knowledge-sharing.

Another aspect that fascinated me was that traditional globe-making had become a lost art – I mean the traditional way of making globes, using authentic materials, copper engravings, and artisanal printing techniques. I felt a sort of calling to revive this tradition, and so I started searching for all the materials needed to recreate a globe as faithfully as possible.

However, Coronelli’s influence on me was not just artistic, it was also entrepreneurial. I discovered that he was a true visionary businessman for his time.

At the end of the 17th century, Coronelli was commissioned to create two gigantic globes for Louis XIV in Paris. After this success, upon his return to Italy, many noble families began requesting personalised globes. In response, he created a waiting list and sent letters to Italian nobles allowing them to pre-order a globe, with the option to paying instalments, with a deposit, or in full. Essentially, he had already developed a pre-order and advance payment system in the 17th century…

Later, he started printing maps for globes, but he also bound and sold them as atlases. He had a printing workshop inside the Basilica dei Frari in Venice, with around twenty people working for him – a full-scale production.

On the other hand, I also discovered that his work methods were not always precise. A few months ago, I was speaking with a London book seller who specialises in antique books, and he told me that he had sold many of Coronelli’s globes and atlases. According to him, while the printing quality was excellent, the organisation was rather chaotic.

Sometimes, orders were forgotten in Coronelli’s workshop, or atlases were assembled with different maps, meaning that no two atlases were exactly the same – each one had a slightly different composition.

It was amusing to hear this perspective: the Coronelli I had studied and admired was a genius, but also a man constantly working against the clock, probably cutting a few corners just to get everything delivered on time!

And in this, I must admit that I see a bit of myself in him. Coronelli inspired me not only as a craftsman and cartographer but also as a man who built a workshop, a network of connections, and a true production system.

Which techniques you adopted for your globe?

Well, the Epitome Cosmografica was published in 1693, and as I read through it, immediately encountered a major difficulty: many of the materials and techniques Coronelli described were taken for granted at the time because they were widely used.

To give an example, it would be like writing a recipe today that simply says, “mix cocoa powder with water”, without explaining how cocoa is obtained or its significance. Now imagine that in 300 years, cocoa is no longer used – someone reading the recipe would feel completely lost.

The same applies to Coronelli: for instance, he mentions a so-called ‘simple glue’ without providing the recipe, because it was something everyone knew how to make in the 17th century.

I had to conduct historical research to reconstruct this glue, eventually discovering that it was made from wheat starch. Another challenge was the technical language, since Coronelli used Venetian terms to describe plants, essential oils, and artisanal processes, which required additional decoding and interpretation.

One of the most interesting aspects of the book is its explanation of how to adapt paper to a three-dimensional sphere from a two-dimensional map. Coronelli instructs that the paper should be boiled in hot water during winter, but not in summer.

This detail made me reflect on the environmental conditions of his workshop in 17th-century Venice – freezing cold in winter, extremely hot and humid in summer – which meant that the way materials were handled changed depending on the season.

I noticed that the same thing happens in my studio today, even though we are in 2025!

Temperature variations affect crucial factors such as plaster drying times, the tension of the paper on the sphere, and the precision of printed lines. If the paper expands too much due to heat, the lines no longer align properly, and the globe becomes distorted. Because of this, I record the temperature of my studio daily in my work diary, so that I know whether it is the right day to print or apply certain materials.

The Materials of Ancient Globe-Making

Was it difficult to find traditional materials for the globe?

The most difficult material to source and reproduce was the paper. It had to be flexible enough to adapt to the sphere, suitable for copperplate printing, resistant to watercolour painting, and able to withstand varnishing.

In his manual, Coronelli does not specify the type of paper he used, but in the 17th century, paper was handmade from cotton or linen. To find the right kind, I travelled to Fabriano, a city with a rich paper-making tradition, and searched for some of the town's paper craftsmen.

While researching, I had an insight: if Coronelli printed the Epitome Cosmografica in his workshop, he probably used the same paper for his globes.

So, I took a copy of the book to Fabriano and compared the watermark of the paper. A watermark is a texture left by the brass wire mesh in handmade paper moulds. After analysing watermarks from that era, we recreated a paper mould using the same measurements and structure Coronelli used.

At that point, an 80-year-old craftsman, one of the last remaining paper mould makers, came into the picture. After some persuasion, he agreed to create one last mould for me, probably the last of his career.

The handmade sheets were produced in Fabriano, then shipped to London, and for three months, I waited anxiously, unsure if they would work. When I finally tested them, they performed perfectly.

Beyond paper, I also worked on pigment research. Coronelli mentions natural earth pigments, so I collaborated with an artisan in Assisi to recreate historical colours. Some pigments had to be modified, as 17th-century paints contained toxic compounds like lead. We replaced these with safer alternatives, maintaining historical accuracy while ensuring non-toxicity.

Another one of the most fascinating ingredients Coronelli mentions is Venetian turpentine.

Venetian turpentine is a resin extracted from the larch tree, and Coronelli cites it as a key component of his varnish, used to enhance gloss and provide greater elasticity to the final coating. This substance had multiple uses: it was employed in the preparation of varnishes and pigments, but also in medicine for its antibacterial properties.

Coronelli lived and worked in Venice, while larch forests are found in the Veneto region, particularly in the Belluno area and the Asiago Plateau, which is also my homeland. There has always been a historical connection between Venice and my region through timber production. The wood used to build Venetian ships and the wooden piles supporting the city’s foundations came from the forests of my area.

When I read that Coronelli mentioned Venetian turpentine in his book, I felt an even stronger connection to this project. It was important for me to return home and source this material directly from my own land, following the same supply process that existed centuries ago between Asiago and Venice.

For this reason, every globe I create contains this ingredient, reinforcing the historical bond between my region and the city of Venice.

What’s Next for Dante’s Globe

Does this globe mark the culmination of your Dantean journey?

When I completed Dante’s Inferno with the violin project, I felt that my journey was not yet finished. Now, with Dante’s Globe, I feel that I have reached my destination, much like Dante in the Divine Comedy, passing through Inferno, Purgatorio, and Paradiso.

That said, I still have projects related to Dante that I would like to develop, including a book on Dantean studies and his universe, a catalogue that collects images of the globe, calculations, and the research I conducted.

Documenting and sharing my work will probably be the next step, because I feel it is time to make my journey public. Writing a book has long been a dream of mine, and I would love to approach it with a personal perspective, connecting Dante not only to my research on materials and Coronelli but also to my homeland.

From an artistic standpoint, however, I believe my Dantean journey ends here.

Is there a chance to see together both your projects on Dante, as you imagined?

Dante’s Globe is a private commission. However, I will create two globes in total – one will remain private, while the second will be part of my personal collection.

This second globe could be exhibited alongside the violins, so yes, there is a possibility of seeing them all together in a single exhibition. It would be very interesting, perhaps as part of the book launch, if that project comes to fruition.

I am not in a rush to organise an exhibition because I want each work to follow its own natural course. Once the globe is completed, it will need time to find the right context.

But yes, I do hope that one day they will be displayed together.

.avif)